The illustration above shows the Mongol Empire at it’s height, in the early Thirteenth Century (1200’s). The Mongols are modeled by self, and are an approximation of certain of steppe warriors including the Mongols. Their horses are small, not ponies, but a hardy breed of horses used to long periods of extreme temperatures. A Mongolian would take five or six horses in a string with them, which allowed sustained movement without tiring the horses.

The Mongols conquests rank as the largest conquest in history. The axes of advance used by the Mongols followed the Silk Road, with a detour here and there, largely because the Mongols were not paid, save by a piece of the booty as prescribed by Mongolian law. The Silk road was anything but silk, it wove its way between the rocks and a lots of hot places (jagged mountains on the rims of large deserts). The terrain that defined the Silk Road, also defines the tactical and operational military operations.

Breakdown of the Silk Road

Transoxiana

In order to make short work of a long road, we can break down parts of the route for ease of study. Since the primary interest is the Holy Land, the Levant, we can backtrack from west to east. There are three major ways from the west to what is called Transoxiana which is the area between the Aral Sea and what is now Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan and reaching into Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan..

This was the far north east corner of Alexander the Great’s conquests and of the Hellenist culture. It lacks defensible borders and the soil is fertile but dry. During the preceding centuries the area became the prize of conquerors from east or west.

The area came under Chinese influence by the Tang dynasty (618-907) and lost to the Arabs in 715 AD. In 763 a Tang General defending the western ends of the Silk Road revolted in the An Lushan Rebellion. The resulting carnage of decades reduced the population, some say, to less than half the original.

As you can see, Transoxiana is a fertile flat area for which access is controlled by a limited number of passes or gates in the Pamir Knot. Hundu Kish area and from Baghdad through present day Teheran.

The Ghaznavids are credited with spreading Islam into the Indian subcontinent use routes at the time of this writing to use the corridor of the Indus River to the Khyber Pass to Afghanistan to supply US and NATO forces currently operating in Afghanistan. The major cities included Bokhara and Samarkand to handle trade going north of the Caspian Sea or to go by way of Teheran or through Alexander’s Barrier.

The Ghaznavids in turn were conquered by Seljuq Turks from their realm in eastern Turkey and Iraq and developed a short lived Kwarezmian Empire founded also by Turkish slave generals. As you can see the basic shape of Alexander’s conquests continue to reappear, as the major terrain features either facilitate or hinder movement by goods, services and firepower.

You notice that the great deserts of Iran and western Pakistan make up big chunks of deserted lands with not much to fight over. Genghis Khan took great pains to wipe this empire out in 1220 AD. The fleeing Kwarezmians hired out as mercenaries moving west and out of the Mongols way. They were hired by the Ayyubid Dynasty, the descendants of Saladin, to retake Jerusalem from the Christians in 1244.

Jerusalem had been recovered by treaty between Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and the Ayyubids, but there were not enough Christians to make the defense of the city viable. The Kwarezmian mercenaries destroyed Jerusalem, burning it to the ground and enslaving all they had not killed, including dogs, chickens, cats and livestock. Then the Ayyubids wiped out the remaining Kwarezmians. Duplicity is not exactly cruel or unusual.

The Pamir Knot

Generally, convex slopes are characteristic of new mountains, the jagged menacing type. Eventually the rocky jagged convex slope gets worn down until it winds up as another sedimentary level.

Fires, however, come in two varieties with respect to the slopes: plunging or grazing. All fires eventually plunge, and some plunging fires are crazing across a convex slope. The tradeoff between slopes and fires is that grazing fire cuts down upright people and forcing them to become a part of the earth voluntarily. Once on the ground, plunging fires which have a small beaten zone, find their targets in low spots on the

Water is the ultimate chisel on land forms, and the courses they take is as valuable to the soldier. Using the handy model (in blue) the fifth type of land is the first type of water, that of a puddle or pool, there are no hilltops of the water (waves don’t count).

Moving across the water courses that follow and make land formations includes: up river, down river, across the fingers (upstream) or across the mouth (downstream), Alexander the Great used his usual side step – side step at the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC. That’s after he passed through the Khyber Pass.

Alexander’s route of march through what is today a very familiar area to today’s warriors, politicians, and contractors. The Kandahar-Kabul route he took is a major line of communications to ISAF forces. From Kabul, one can go in multiple directions, and conversely if you want to go to Kabul from India, one goes through the Khyber Pass or to the south through the Dolan Pass.

Alexander crossed through the Dolan Pass in 329 BC and returned through the Khyber Pass in 326 BC.

Since water courses dig the valleys, they run parallel to the ridges that were defined by the erosion in the first place, Young mountains such as are found here, are jagged.

Alexander followed the Indus south to the present coasts of Pakistan, Baluchistan, and Iran using naval forces in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. If Alexander’s troops had not asked for a time out, Alexander would have made contact with the Chinese by going through any of a number of passes through these giant mountains.

This is a corridor that starts (or ends) in Kabul and follows the Panj River towards China. There is practically no usable roads there, but this route is now the place where China and Afghanistan meet, at the end of a long finger on the political map of Afghanistan.

Maps of the growth of China along the Silk Road show the history of using this corridor and Fergana Valley in Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The Tang Dynasty had extended it’s power well into the other side of the Pamir Knot.

The expanding Abbasid Caliphate that had conquered the Sassanid Empire base mostly in Iran, ran headlong into the Tang Dynasty in the Battle of Talas in 751 I which the Chinese lost their hold on the western side of the Pamir Knot. Not uncommon in tales of this part of the world, the Chinese became outnumbered two to one by the defections of private military companies (mercenaries) and the defection of coalition troops from the Fergana valley.

Shortly afterward, in 755 AD. Chinese general An Lushan of Sogdian ancestry (that area just north of Afghanistan including the Fergana Valley), revolted against the Tang Dynasty and fought a series of wars resulting in a dramatic loss of Han Chinese presence in the Far West.

Afterwards, these losses made it harder for the Chinese to resist encroachments on or from the Silk Road. The Chinese seizure of Tibet in 1951 and the colonization of Tibet with the Han, is a classic example of people who know their geopolitical priorities.

Fergana Valley

To the north of Afghanistan lies the Fergana valley, one noted for good agriculture land and its use. During the period of the Crusades, it was one of the more traveled routes of the Silk Road. The Chinese destination to the East is Kashgar where both routes come together.

The Takla Makan Desert

The next stage of the main Silk Road is anchored on Kashgar and travels either north or south of the desert, along a string of oases close to the edge of the desert. Other branches of the Silk Road avoid the rough terrain for a wide sweep across the Russian Steppes before dropping down to the Silk Road.

One of the more famous routes from the steppes is through the Tsungarian Gate. This picture is directed to the southeast by east as indicated in the small insert.

Some extraordinary work at this site.

The Gansu corridor was given up by the Chinese as a result of the An Lushan rebellion which left the Silk Road under the control of competing Turco-Mongol tribes.

The Ordos Loop

The Yellow river system and its tributaries such as the Wei, was the birthplace of China. The weather of the Ordos desert and to the south was unpredictable and variable. The Lower Reaches of the Yellow River whiplashed north and south of the Shantung Peninsula killing millions each time it flooded.

In order to make maximum effective use of widely fluctuating weather conditions which resulted in loss of life and property, the Chinese developed large public works for flood control and irrigation. As elsewhere in the world, this created the need for a central authority to allocate resources (capital, people, equipment) resulting in strong regional governance.

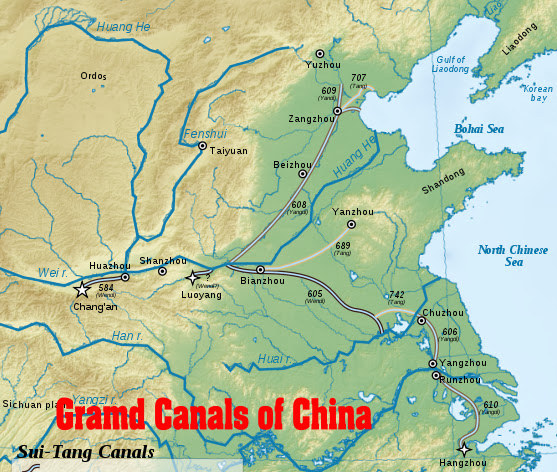

In addition to great irrigation works, early Chinese emperors started building giant canals five hundred years BC, which continues today.

The river systems that define Chinese topography include the Yellow, the Yangtze, and Pearl River. Shanghai rests on the Yangtze, and Canton on the Pearl.

The Yangtze creates an east-west line of demarcation between North China and South China. Over the centuries, the regimes in the North have, from time to time, been unable to conquer the South.

In addition to the extremes of weather, China was faced with huge invasions of horse mounted light cavalry. From time to time, a Chinese emperor would hire out private military units (mercenaries) to put down revolts, or to fight other horse mounted raiders form the North.

Thus the Great Walls of China were built to extend the effect of the Himalayas that restrict the avenues of approach to China to the Takla Makan Desert and Gansu Corridor. Based on the fortunes of the times, there are many different walls of China, but generally east west taking advantage of high ground to observe and control traffic below or through.

By the time that the Crusades were starting, China was divided into three parts, and the Silk Road was under control of other nomadic tribes, other than the Mongols. That changes radically after 1200 with the explosive rise of the Mongols.

The story of Genghis Khan’s problems was to get rid of the threat of the XiXia Kingdom before taking on his arch foe, the Jin or Jurchen Dynasty. The Jurchins were booted out of China by Genghis Khan but it should be noted that they would return as the Manchu or Qing Dynasty that ruled China from 1644 to 1912 (not counting the short lived Manchukuo dynasty under Japanese control in WW2.

This trip from the Levant to China is relevant as within the Thirteenth Century the Mongols would sweep from attacking Japan and Vietnam to Baghdad to the Levant and to seize and burn Kiev in the Ukraine.

Oh yes, Templar Knights faced off with the Mongols at the Battle of Leignitz (Legnica, Poland) on April 9, 1241. It didn’t work out well.

nnDnn

No comments:

Post a Comment